Follow the link!

Final Project – Whitman in American Media

Finding Whitman

Filmed in Marye’s Heights at the Fredericksburg Battlefield. My camera makes me sound like I have a lisp, I don’t know why.

My Contribution to the Whitman Legacy

Around the middle of the semester I was inspired to write this poem. I was in a very “Suck it Walt!” mood.

*Title stolen from inspired by Dr. Scanlon

My Womanly Whitman

You say you speak for the masses,

that your words bodies for our bright souls

but my body is crude at your hands, unskilled

in curves and perfection.

You say you contain multitudes, but you can barely envision me.

You did not know, but I have contained multitudes as well.

I was there in your masculine rough hewn hills, rolling

mountain lines, painted into red sand deserts and sculpted

into warm stucco walls, in damp depths of canyons

that descend beyond the limit of your thoughts.

And yet, I have seen you only in broken mausoleums,

carved in granite and steel, rotted in petrified logs

invaded by time.

You think you have built this America without

me, and invited me back to admire your craftsmanship

and sew its garments, but I am not a visitor,

or a servant, or a nurse who longs to be buried with her soldiers.

I am not born out of your cracked skull, made whole only

when you exalt the beauty of my sons.

You, who do not believe in the god stuff, should have known

that I came before you.

But you, slouching, cocked brim, good grey wise uncle Walt,

I can’t revere you, I

can’t believe you, you

who have never known me under your fingers in the night, you

who have only known me through idle conversations

with your married projected lovers.

Erin for 11/17

Preface to this blog: I got a little off-topic. Also, reference to Bruce Springsteen may seem out of the blue if you haven’t read my previous post on an article I read comparing Walt to the Boss, which can be found here.

One of the things that I find fascinating about Whitman is that, while I’m not very much of a patriot, I can jump on his America-loving train. He writes beautiful sweeping visions of the nation, and he includes me in them (well as a woman that’s somewhat arguable, but I’ll avoid that line of thought this time), and it feels ominous and powerful. Normally I’m all about some “the American dream is dead!” poems/songs/books what have you, and yet somehow Whitman can get me away from that, if only for a short while. However, when I read Whitman’s work, I don’t envision it applying to America now. I apply it to some idyllic America of long ago, one that does not, and will never exist again.

Obviously it’s not just me who has this preference for the depressing view of America, since so many people write about it. It got me thinking though, did society really change that much from Whitman’s time to now that we’re so much keener to bash our country than talk about how great it is? What happened that created such a giant shift? It can’t be that things are so much more corrupt now than back then, or harder or more horrible. In Whitman’s time they were dealing with tenement houses and awful working conditions, racism, bad pay, unemployment, the same things that Bruce Springsteen and others write about. Yet something tells me that if Ginsberg or Springsteen went back in time, their take on America wouldn’t resonate the same way that Whitman’s did, and vice versa.

Basically every idea I formulate as a reason for this shift has an equally valid opposition. I wondered if it was because there still seemed to be so much opportunity left in America during Whitman’s time. There were parts of it that were still unexplored, that hadn’t been carved up into states yet. Maybe the “American dream” is something that people still widely believed in. Then I am reminded of Dr. Rigsby’s course on American Realism, and I’m pretty confident that the people of Whitman’s time were aware that the “American dream” was something only available to those who were lucky, or were already privileged. Even now, while many people recognize that the ideal of the American dream is just that, there are still people who come to this country because of the belief that you can do anything here.

Another thing that I have considered is that perhaps people during Whitman’s time people needed an uplifting view of America, especially when it got to the Civil War. Things were bad for pretty much everyone at that time, and to be included in Whitman’s ideal vision of America was what they needed. Maybe we can only enjoy Springsteen and Ginsberg because we come from a position of privilege. Most of us will never have to go to war, or work in a factory for minimum wage, but we can look at it from a distance and get mad about the injustice of it all. We can criticize the government without being in danger of being imprisoned or persecuted or shunned for it. On the flip side of that though, that doesn’t include the people who aren’t privileged, who Springsteen centers his narratives around, and who still enjoy his music.

So in the end, I have no concrete ideas about why this shift has occurred. Why can I accept Whitman’s view of the America in the past when I know it’s not really true? Why does “Song of Myself” make me just as happy as Ginsberg’s “America” or Springsteen’s “No Surrender?” I don’t know. I put it to the rest of the world to sort these things out for me.

Erin for 11/10

The prompt for this week reminded me of something I had thought about while reading about the ARG being sponsored by Levi’s right now (the GO FORTH treasure hunt game that goes along with those commercials). In the game someone was given an 1882 edition of Leaves of Grass to use as a cipher for one of the clues. I’m sure that 1882’s are easier to come by so that’s why it was used, but my initial reaction was “What? Why the heck would they use that edition, I didn’t even know that one existed!” We have talked about the “deathbed” 1892 edition, the “Walt Whitman, recently immigrated from an unknown planet” 1855 edition, and the “strange” 1867 edition, but not really much else. So I went on the Whitman archive, and read “about” section for that edition, and then I felt kind of dumb. The 1882 edition and the 1892 edition are basically the same; there are no significant changes to the text. I may have missed this in class somewhere, so maybe this is only news to me, but I found that interesting. I also found it interesting that apparently the 1882 edition was set to follow an almost narrative pattern. The clusters were arranged in such a way as to have a definite build-up, with Drum-Taps as the climax, and then resolution in the Lincoln poems and other following clusters. Originally my perception of the various editions is that they should be looked at as specific representations of different times in Whitman’s life. He adjusted each edition to his particular purpose and message at that time, so it seems logical to view them that way. Knowing that the deathbed edition doesn’t follow this thread complicates things. Many people view this edition as the “definitive” edition, and yet fundamentally it’s different from all the previous ones. The fact that it’s based in a narrative, and none of the other editions are, makes it harder to compare to the rest of them. There’s just a completely different motivation going into the assembly and ordering of this book. In essence, I don’t ever think we can say that there’s a definitive Leaves of Grass. They each mean different things to their different times. Personally, I like the 1855 Song of Myself better, but as I mentioned in my last post, the Song of Myself from 1892 is powerful in its own ways to me as well. There’s so much layering between each of these editions that by picking one of them as the text that we should go with above all the other texts seems rather unfortunate and narrow minded. I like the idea, even though it’s a frustrating one, of having to just pick things out of every edition, taking them each for what they are at each separate time. Whitman gave us something that no other poet has with these multiple works, and I think it’s important that instead of trying to whittle it down, we appreciate it in its “multitudes.”

Erin for 11/4 (in which I get a little blubbery)

In reading the deathbed version of Song of Myself, I don’t know how much the speaker had changed in actuality from the 1855 speaker, and how much change I was simply adding in from my knowledge of Whitman, and the relationship I now have with him and his work.

In reading the 1855 version, I had no real preconception of Whitman, no real knowledge of who he was, and what little I did know of him had no bearing on what I thought of the poem, or how I interpreted it. I read Song of Myself viewing the speaker as an anonymous being; since I had no real idea of Whitman, I only placed him as a name in the narration. In reading the deathbed edition however, it’s just the opposite. I have a very definite idea of who Whitman is, and I can’t help but let my feelings and thought about Whitman influence how I see the speaker. So it’s hard to say how much of the changes I noted were actually changes, or me just viewing things differently.

I noticed that even though many of the powerful lines are the same, I read them in a completely different way in the DB edition. I often would read a line, and then double check the 1855 edition just to see if it had been changed at all. I was somewhat surprised that the lines and images jumping out at me were often the same in the 1855 as in the DB edition. It was interesting to me though, that many of the lines and verses I underlined or took special notice of in the DB edition were completely different from ones I had taken note of in my reading of the 1855 version. Knowing all the things I do now about Whitman’s life, different things stuck out to me.

“I am an acme of things accomplish’d, and I an encloser of things to be.” (239)

This line appears in both the 1855 version and 1891 version. At first when I read this line in the 1891 version, I thought perhaps he had added it in, and then found out the same line, unchanged, was in the 1855 version. I couldn’t believe how differently I interpreted it. In the 1855 version I see a young Walt, a little bit pompous, exalting himself, his poetic career in front of him. In the 1891 version, I see the older Whitman, looking back on his career, greeting the future of America, himself, poetry, anything. I want to know if Whitman reread these lines and thought of his younger self, or if he, like me, saw that he had changed, and yet the line still meant the same thing really. Maybe this is why Song of Myself still speaks to me, over 150 years after it was published. Because it could still speak to, speak of, Whitman, even 40 years after he had written it originally. It occurred to me around this point that not only was I projecting my knowledge of Whitman onto this reading, but also the knowledge that he was near his death. That line definitely stuck out for that reason.

As far as the actual changes I saw in the poem, most of them seemed to give the speaker more confidence. Whitman eliminated the ellipses (something which I saw changed in other poems) and some of the commas as well. He also compacted the stanzas and lines from the earlier edition. There were less lines just free floating. At times in the 1855 version, while the speaker was very sure of himself, it seemed that often there were time when the speaker was testing the waters; it didn’t seem like he was always completely behind the ideas being thrown out. This speaker is confident and wise in everything he says. There are no drawn out pauses of consideration, just a straight forward laying out of what he is trying to say to his audience.

There also seem to be less references to God, possibly in relation to this confidence. Instead of in the 1855 edition where Whitman says

“Shall I pray? Shall I venerate and be ceremonious?” (45)

In the DB edition he asks

“Why should I pray? why should I venerate and be ceremonious?” (206)

This more direct tone seems to be in connection with the more knowledgeable and wise speaker of this edition.

There were other small changes that influenced by interpretation of the speaker. On 214, the line

“I hear the chorus, it is a grand opera,

Ah this indeed is music—this suits me.”

felt very powerful to me. I immediately looked it up in the 1855 edition, to see that the last half of the second line “—this suits me” (54) had been added on. I could very much see the speaker I had been envisioning—the aged, wise Whitman—saying this line. Maybe it just seems like something an old man would say, I don’t know. To me it seemed like something Whitman would say, from what I know of him anyway. It gives me this very relaxed, accepting sense of the speaker, falling in line with what I have been thinking of Whitman.

Even reading the last section of the poem, about looking for Whitman under our boot soles, etc., gave me a completely different feeling. I knew they were the same lines that I had read from the beginning of the semester, but it didn’t change the fact that I felt them so strongly this time around. Not to say they weren’t strong from the beginning, because they were, but imagining the good grey poet instead of the young, well, also grey poet made me a bit emotional. It was then that I finally concluded that I would never know for certain how much the speaker had actually changed.

I don’t really know how to end this, other than to say that this is probably an awful mess that doesn’t make much sense. I tried. Perhaps I will post more on this later, since I am already at a very substantial amount of words. There were a lot of other small changes I wanted to talk about. So in conclusion, I need a follow-up post.

The Good Grey Poet Vs. The Boss

While waiting for my DC pictures to upload on Flickr/Facebook, I thought I’d do a quick post on an article I read today.

Last night I started poking around on databases for ideas on what I should do my final project on, and I happened to stumble on an article called “Whitman, Springsteen, and the American Working Class” by Greg Smith. I had to read this for two reasons. The first being that my mother is a HUGE Bruce Springsteen fan, and has spent the last two years converting me so that I will accompany her to shows on his cur

rent tour with the E Street band (we’ve been twice in the last year, and we’re going again in November) and the second reason being that it’s a pretty interesting comparison, considering Bruce Springsteen is kind of like the Walt Whitman of our (our parent’s?) time in the sense that America is his schtick.

Older picture of the Boss circa the late 70's early 80's. Did I mention I totally have the hots for him?

A young photo of Whitman for good measure.

The article discusses the success of the respective writers to reach/capture the American working class, something Whitman, as we all know, desperately wanted to do. Smith says that Springsteen wins this fight on both counts, and I have to agree. While the article mostly focused on Springsteen, it did bring up an interesting contrast between Walt and Bruce. Whitman represents the idealized American Dream, where America is continuing to expand, the industrial revolution is still in motion, and the working man is happy and robust (Smith refers to “I Hear America Singing”). Springsteen is concerned with destroying the fallacy of the American Dream, and truthfully portraying the American working class, destroyed by their blue collar jobs. Smith makes no mention of Whitman’s war poetry (I suppose that would be a bit of a tangent considering it was focused on the working class) but I wondered what comparisons he would have drawn between Springsteen and Whitman there. While he may have romanticized the working man, Whitman was of course dedicated to portraying the horror of war, just like Springsteen sings about the effects of the Vietnam war.

You can read the article here.

By the end of the article I was prepared to start working on in-depth comparison of Whitman and Springsteen, but I’m not sure there would be any real value to that analysis except that it would amuse me…

Erin for 10/27

I don’t know if this is sad or disturbing, but at times I really identify with Whitman’s obsessive fanboy love for Lincoln. While I’ve never fawned over a politician, there are a few musicians that I’ve gotten a little unhealthily obsessed with over the years. This summer alone I drove four hours to DC to see my favorite artist, and then four hours again two days later to see him again in NC. So I can’t really say I blame Whitman for collecting pictures of Lincoln and picking his favorites, and waiting on street corners for him. I would probably do the same thing. Lincoln was America embodied to Whitman, how could he not want to stalk him at every possible opportunity? Whitman wanted a united America, where everyone loved each other and frolicked in the fields and talked about how awesome and beautiful the U.S.A. was. Bring in Lincoln, who is trying to do just that, but maybe without the poetic frills in mind. I had kind of forgotten until reading the article about Lincoln and Whitman this week that things between the North and South had been festering for a while. Thinking back to when I originally read Song of Myself and poems earlier in the semester, I hadn’t really considered that. Thinking about it now though, it makes so much sense why Whitman would place so much importance in Lincoln. Here was a man, trying to unite America and expand it as Whitman envisioned.

In class we’ve often made fun of Whitman for being so much of a creeper about Lincoln in his writings. It occurred to me though that one of the possible reasons it seems like that is because Whitman is addressing one particular person through his writing in these instances. Whitman usually refers to an ambiguous “you,” which is often plural. We don’t know Whitman’s true relationship to the “you” in his writing. So then when reading Whitman’s poetry about Lincoln or his writings about Lincoln, it comes off seeming a little weird, because we know that Whitman never met Lincoln, and only saw him a few times, and yet refers to “him I love.”

Even still though, his love for Lincoln that he expresses through his poetry is definitely different from the Calamus love and love for the soldiers he writes about. He seems to acknowledge that he has never been in close contact with Lincoln by leaving out physicality from these writings, or perhaps signals to the fact that this kind of love is different, a reverent love. I was poking around on the internet to see if there was any symbolism for the lilac, and according to several sources, lilacs usually represent early love or first love. Often “first love” gets romanticized and idealized, and putting that alongside his relationship to Lincoln, it seems like he’s trying to portray a pure love for this man that he didn’t know, leaving out sexuality and physicality.

I loved where Whitman wrote about gathering armfuls upon armfuls of lilacs and bringing them to the coffin, it was so touching and romantic in a strange way. Especially after seeing some of the pictures of Whitman yesterday and just the general experience, I could perfectly see him with his arms full of flowers and his beard, laying them down for Lincoln. I don’t really know what to say other than it made me kind of love him for it.

Belated Partial Field Trip Post

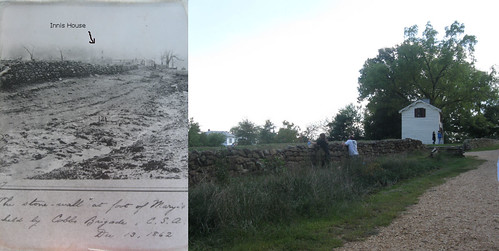

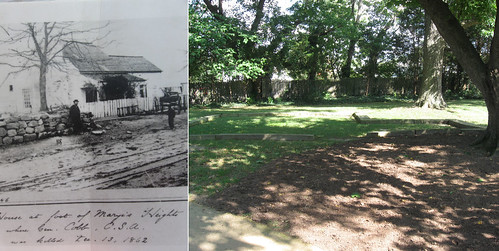

When we were at the Fredericksburg battlefield the park ranger there let me take pictures of the photos of the pictures she showed the tour group. I took a few of them and then lined them up with current day pictures:

This one isn’t of the battlfield, but the man on the left was a confederate soldier who went out on the battlfield and gave water to wounded union soldiers. I want t say he was called the angel of Fredericksburg, but I’m not sure that was his name. The picture on the right is a monument to him.

The picture on the left is of the battlefield wall with the Innis house in the distance. The right hand picture is of the same wall with the Innis house.

This photo is of the Steven house, which you can see the foundation of on the right.

Picture of what the battlefield originally looked like, and a picture of what’s there today.

You can see the images at a larger size if you go to my flickr account, I think if you go here you should be able to see them. Hopefully I’ll be adding more picture from the trip within the next two days.

Cultural Museum Entry: Surgical Saws in the Civil War

Background:

Surgical saws and tools have been in use since at least 3000 B.C. The first known surgical armamentaria, the equivalent of a Civil War surgeon’s kit, was found in Pompeii, and dates back to 79 A.D. (Kirkup 21). Surgeon’s tools at the time were composed from many materials, including copper, bronze, silver and steel (29). It was typical for surgeons to choose their own material for their tools, as well as help craft them, so there was a lot of variation from country to country. In the 15th century, tools became slightly more standardized, and the first widely used saw was the bow saw. This instrument was often highly ornamental, and was often extremely long, with some models reaching up to 67 cm. Surgeons were advised to keep an extra blade handy when performing surgery, as the blades would often snap during the procedure, due to their length and lack of reinforcement. Though the ornamental saws were quickly done away with, as the decorations often tore the tissue around the amputation site, the lengthy bow saws remained the popular choice for the next two centuries (387).

Surgical Saw Development Leading up to the Civil War:

The 18th century saw the rise of smaller saws with better adapted features. In fact, many of the saws that were used in the Civil War are very similar to those used today. The biggest difference between past and current saws is that while current saws are made from stainless steel, saws from the Civil War era were nickel based (Belferman 1). While the exact number of amputations during the Civil War is unknown, it is estimated to be around 70,000 total and accounted for 75% of all major surgeries performed (Trammell 46). Amputation was the standard treatment for any wound that created a compound fracture. Remarkably, around 75% survived the operations. This is most likely due to several advances made in surgical saws and tools just prior to the Civil War. In his book American Surgical Instruments, James Edmonson states that craftsmanship of surgeon tools in the 19th century was greatly improved and expanded due to new manufacturers, as well as an influx of immigrants who brought their own particular skills and knowledge from their native countries, and the older more established companies mixing together (44). Many advances and changes were also made during the Crimean War by British surgeons. Several major changes included the invention of a frame saw with an adjustable rotating blade in 1850 by the Butcher Company (Kirkup 202). The rotating blade gave surgeons the ability to be more precise in their incisions, as well as allowed them to cut out damaged tissue in such a way that sometimes did away with the need to amputate. A second major change to the saw was the rise in popularity of the pistol handle.

The handle was much easier to grip than the previous t-shaped handles usually featured on saws. Another major shift in saws had to do with the introduction of tenon saws. Tenon saws were smaller, and more accurate than the bow saw, which was still in heavy use. The saws were much less cumbersome, and were reinforced along the back. This allowed for more movement of the blade, as the blade could often pivot on the reinforcement, which helped the surgeon avoid damaging the soft tissue around an amputation site. The reinforcements also did away with the problem of blade breakage, which was the biggest downfall of the bow saw. Tenon saws became the most commonly used in Britain, and were widespread in the U.S. as well, though they were not nearly as popular in continental Europe (203).

Use in the Field

Surgeons were always equipped with a surgeon’s kit, a case that contained around 30 different tools (Trammell 51). The U.S. government purchased large numbers of specially manufactured kits from instrument makers at the time to distribute to field surgeons (Edmondson 50). Several main manufacturers of surgeon kits at this time were Jacob H. Gemrig, Horatio G. Kern, George P. and Henry C. Snowden and Dietrich W. Kolbe (43). These kits were usually made from mahogany and lined with velvet. As many Civil War doctors would later note, this was not particularly conducive to maintaining sanitation, as the tools would often go back into the kits after being hastily wiped off. Most kits consisted of two saws, the capital and metacarpal saw, along with many other forms of amputation knives, scalpels and other tools. These saws would be the capital saw and the metacarpal saw.

The capital saw was used for large bones, whereas the metacarpal saw was used for smaller bones. An amputation could not be made with only these tools alone though. A surgeon’s kit was supplemented with various amputation knives and scalpels, as well as a tourniquet and forceps (Trammell 51).

Works Cited

Edmonson, James M. American Surgical Instruments. San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1997.

Trammell, Jack “‘Life Is Better Than Limb’.” America‘s Civil War 21.6 (2009): 46-51. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 20 Oct. 2009.

Kirkup, John. The Evolution of Surgical Instruments. CA: Norman Publishing, 2003.

Belferman, Mary. “On Surgery’s Cutting Edge in the Civil War.” Washington Post 13 June 1996.